Originally published in the Marina Times San Francisco in September 2013

I don’t believe in art. I believe in the artist. —Marcel Duchamp

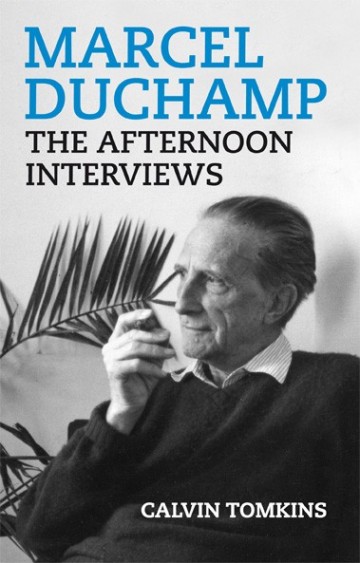

When he first met Marcel Duchamp in 1959, Calvin Tomkins was not the famous art critic he would later become. In fact, at the time, Tomkins knew nothing about art. His meeting and ongoing friendship with Duchamp, agruably one of the most acclaimed artists of the twentieth century, would change the trajectories of the lives of both men.

Marcel Duchamp The Afternoon Interviews is a collection of talks between Tomkins and Duchamp conducted in 1964 and arriving like a message in a bottle in 2013 via a new publication from Badlands Unlimited. Duchamp weighs in on diverse topics including money, his interest in chess, conceptual art and influence (something he denied that he had.) A new introduction includes a recent interview with Tomkins reflecting back on his time with Duchamp. During his career as an art critic the author claimed “I never found anyone who was less burdened by ego than Duchamp.”

A pioneer of Dada and conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp made a name for himself in 1912 when his cubist painting Nude Descending a Staircase created controversy. The resulting notoriety landed the painting in the legendary Armory Show exhibit in 1913. Ultimately, Duchamp wanted to return art to the service of the mind. He derided what he called “retinal art” and instead explored work that emphasized ideas over form. His “readymades” fulfilled the task. Found objects somewhat manipulated and taken out of their ordinary context served ideas instead of the eye. A shovel hanging from a gallery ceiling became menacing when given the title In Advance of the Broken Arm. The mundane aspect of readymade objects communicated the artist’s deadpan sense of humor while blurring the boundaries of art and life.

During these talks, Duchamp provides insights on one of his most famous works, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass). Details about the process of creating the painting, the two panes of glass, and the accident leading to its breakage and his meticulous repair of the work are told with an unusual detatchment and concern mainly for the owner of the piece. Through reminiscence, Duchamp delves into his philosophies about the role of the artist, productivity and the limits creative people impose on their own minds. Profound topics indeed, but Duchamp speaks with a relaxed effervescence that keeps it entertaining.

The Afternoon Interviews is a rare glimpse of Marcel Duchamp not as an enigma but as a person. Key Duchampian concepts are made readable through Tomkins and Duchamp’s conversational ease creating a must read for the modern art lover.