First published in the San Francisco Northside in August 2009

Honor the error as a hidden intention. —from Oblique Strategies, a set of published cards created by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt

in⋅cu⋅nab⋅u⋅la:

/ Show Spelled [in-kyoo-nab-yuh-luh, ing-]

–plural noun, singular -lum /-ləm/ Show Spelled [-luh m]

- extant copies of books produced in the earliest stages (before 1501) of printing from movable type.

- the earliest stages or first traces of anything.

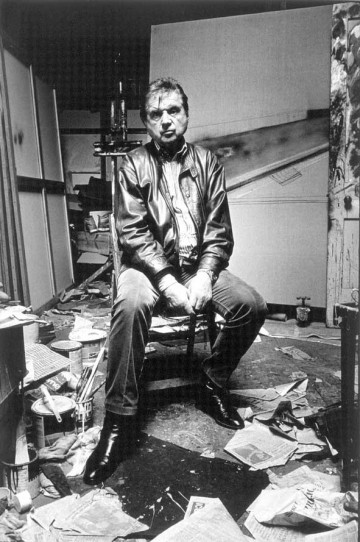

During the life of the painter Francis Bacon, journalists became fond of photographing his studio which was famous for its unique disarray. Piles of photographs, books and newspaper clippings were strewn, torn and spattered with paint creating a veritable archaeological dig of source material for Bacon’s work.

Francis Bacon didn’t work from life. Rather, he used imagery to inform his paintings by surrounding himself with a living collage of reference material. The authors of Incunabula describe the deliberate means in which Bacon’s studio was recently disassembled and scrutinized to achieve a glimpse of the artist in process.

Bacon’s paintings are a subconscious, dreamlike view into floating interiors featuring twisted, flesh like appendages sometimes resembling people or hanging slabs of meat in a slaughterhouse. The figures often appear pushed into strangely angled corners or trapped in undefined violence, yet the compositions are rendered with an air of serenity.

The evolution of Bacon’s paintings is revealed in random selections of source material. For example, the books that cluttered Bacon’s studio were deliberately shelved with the spines facing away from his sight. A book would be selected at random, pages torn, and imagery folded into the shape of a cone designed to stand beside Bacon’s easel without falling down. The abstraction created by the folds often translated into the final painted image-another degree of separation from the props that aided in creating the dreamlike quality of his canvases.

In Incunabula, source materials sit on the pages side by side with the paintings that developed from them. On one page, a torn newspaper photo showing an opera singer in profile with outstretched arms is transformed into a sphinx, the head further transformed to resemble a second photograph of one of the artist’s friends. Thus, a portrait is created. A photograph with sharp diagonal folds becomes a self-portrait of the artist with similarly distorted features as in the photo. On another page, a clipping of hanging birds stripped of their feathers becomes a painting of a red cubist interior featuring a trompe l’oeil bird hanging in space. Here the authors take a biographical aside and explore Bacon’s interest in meat imagery: was Francis Bacon fascinated with hanging carcasses, (which became the trademark image in his paintings), because his namesake, Sir Francis Bacon, died of pneumonia after stuffing dead birds with snow in an attempt to find a new way to preserve meat?

Francis Bacon the painter made no secret about the reason his studio was kept in what might at first glance appear to be only cluttered wreckage. The environment gave him the impulse to create order out of chaos. Paintings were the result. His studio could be regarded as his final work of art, a work that will remain a gloriously unfinished testament to an artists’ creative process.