Originally published in the Northside San Francisco in December 2009

I paint things as real as I can. —James Rosenquist

In his newly published memoirs, James Rosenquist tells the story of his rise to art fame from humble beginnings. Painting Below Zero chronicles the origins of pop art through anecdotes centering around Rosenquist’s role as a painter living on the periphery of the new.

He could have easily made a living as a story teller if he didn’t possess an early aptitude for art. Born in North Dakota in 1933, Rosenquist writes about the Midwest as a great generator of fantasy. Totally flat land existed like a blank screen inviting inventions and visions into other worlds. He tells tales of the strange things that seemed to happen all the time; once in 1938 a meteor landed a few miles away from his house, hitting a woman on her hip while she was sleeping. She somehow lived.

The flat expanse of the land easily translated into what later became his monumental canvases. Rosenquist traveled the country in the 1950’s painting billboard advertisements. This became an unconventional, grueling art school that set the stage for his large scale works that would later dominate his fine art career. Presented with an image on a scrap of paper, a bottle or perhaps no source material at all, Rosenquist’s employers would command him to replicate any given object in paint, sometimes several stories high. He describes the subculture of hobo painters that traveled around the country painting advertisements and improvising images with the agile versatility of jazz musicians trading riffs. Creativity was sometimes required under harsh conditions. Rosenquist suffered from frostbite, heatstroke, and dangerous h eights that were all risks of the trade.

In 1960, Rosenquist made another risky leap into the realm of fine art, quitting his job to paint full time. A quick succession of serendipitous encounters put Rosenquist in the same social scene as newcomer artists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. During their lifelong friendship, Rauschenberg and Rosenquist stretched the boundaries of what constitutes art. Painting Below Zero retells a famous exchange between the two artists while in Rauschenberg’s studio:

“I want to show you my new work,” Rauschenberg said. It was six bamboo poles leaning against the wall with strings and tin cans hanging from them. “Bobby”, I said, “I’ve been looking at this piece for an hour and I don’t get it.” “Well”, he said, “I know you put things on the wall before you know what they are, too.”

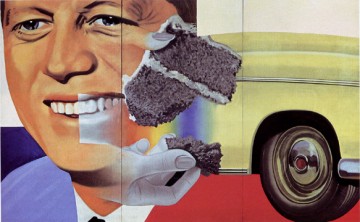

Rosenquist naturally sought out the anonymous advertising imagery he was accustomed to painting and combined them in unusual juxtapositions to create a new visual language. Paintings based on collages effectively mirrored a fragmented contemporary world full of interruptions, noise and consumerism. He quickly became part of the pantheon of pop art, held in the same regard as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. A tortured artist he is not. In his down-to-earth, humorous style he explains that great art is not a product of suffering, but great art is made in spite of suffering.

James Rosenquist’s life intersects with many of the major events of the mid-to-late twentieth century with a zigzagging randomness that seems to make perfect unlikely sense, paralleling his paintings that contrast equally unlikely images in large scale abstractions–Cadillacs with spaghetti, for example. Somehow, he makes it all seem as real as it gets.