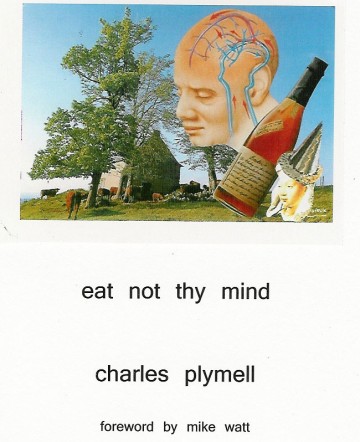

In His Own Time- Charles Plymell’s new volume of poetry “Eat Not Thy Mind”

Originally published in the Northside San Francisco in June 2010

Poet, publisher and artist Charles Plymell’s new volume of poetry Eat Not Thy Mind is part of a trajectory of work spanning more than 50 years. During that time, Plymell has pioneered new creative frontiers. He was a part of the 1950’s and 1960’s subculture in Kansas and California developing what became a permanent affiliation with the Beat generation. As a publisher, he was a part of the underground comics movement printing the first editions of Zap Comix with R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson in 1968. He founded Cherry Valley Editions with his wife Pamela Beach Plyme ll and together they printed books by writers such as William Burroughs and Herbert Huncke. Plymell has written many books including the novel The Last of the Moccasins which was published by City Lights in 1971.

Eat Not Thy Mind is a co-production of Ecstatic Peace Library based in New York City and Glass Eye Books based in Florence MA. Ecstatic Peace Library is a collaboration between musician/artist/poet Thurston Moore and publisher Eva Prinz, and Glass Eye managed by Byron Coley. Ecstatic Peace Library is a new enterprise as of 2009 and is involved in publishing art, underground culture and poetry books. Avid collectors of all things Plymell, Ecstatic Peace and Glass Eye are also working on a descriptive checklist of the works published by Cherry Valley Editions. They also hope to release a definitive recording of Plymell’s readings (with musical accompaniment) in 2010. Charles Plymell recently spoke with the Nort hside’s Sharon Anderson about his latest endeavor.

Tell us a little bit about how you got involved with Glass Eye/Ecstatic Peace publishing.

Laki Vazakas lives and works near Florence, MA and took me and mutual friend, Grant Hart, to perform there and videotape performances when Grant introduced me to Mike Watt. This is how I eventually came to know Thurston Moore. The situation developed where old friends met new friends. They have some rooms in a huge factory building in Florence that has been turned into arts spaces. Their Yod Space houses Glass Eye/Ecstatic Peace productions and performer’s visits. The rooms are stacked from walls to ceiling with books, art, and albums mainly from beat/punk/hippy periods that can be seen in many videos and television specials that Thurston narrates. This repository of artifacts extends to Thurston’ s private libraries of music, art and literature. Combined, it represents a period and genre more extensive than most university libraries. A collector himself, Thurston not only had some of my works I had forgotten about, but the printing plates I ran them on. Geographically, the region is probably one of the most literate in the country, and I was surprised that my audiences there had plenty of my collected works at my readings.

How long did it take you to write Eat Not Thy Mind and what time period does it represent?

Most of the book has crept through my consciousness in the last year or so, repented, revised, replaced, re-arranged, recast, etc. I did a poetry reading during Byron Coley’s “No More Bush Tour” in 2008. Mike Watt was on tour with Iggy and the Stooges in nearby Baltimore, so we got together in Philadelphia and Mike played bass while I read. It was during this time that I conceived most of it.

You’re also a visual artist and a publisher. How did you first become interested in publishing?

I’ve mentioned my publishing stories somewhere, I think, but the beginning was in Kansas when I got a job running a printing press in-house at a hospital by lying that I was a printer. I worked nights and took courses at a nearby college and met two poets I thought were the best in the land (still do) and a couple of professors. The obvious next step was to print their poems on the press at night when no one was around. I worked at San Francisco State which had a few presses. I even worked at Foremost Dairies in San Francisco and became such a good worker that I got a job with Standard Oil across the bay. They hired me to run their Printing Department.

You’ve consistently been at the vanguard of major art movements. I’ve noticed that your creations are always forward thinking and still consistently geared toward the new. Given this, how do you regard what could be called “Beat nostalgia”? It seems like everyone else spends a lot of time thinking about your past while you’re forging ahead and pursuing new ideas.

I never gave it much thought. I always maintained a peripheral profile and the thought of being labeled in a group just didn’t occur to me, so I never felt I was a part of it

You do have a deep connection to the Beat scene in San Francisco, a literary movement fraught with nostalgia! For a time you lived with Allen Ginsberg and Neal Cassidy on Gough St. How did you become affiliated with the Beats?

It might be important to note that I was making my own scene when the major Beats sought me out in 1963 by actually showing up at my door, not the other way around.

Yes, that’s an important distinction.

That timeline gets confused. Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Whalen, McClure’s, et al. rang my doorbell at 1403 Gough St. and said they heard I was having a party. Yes I was! I said come in. I had met the McClure’s and some other poets of the Auerhaun Press but I hadn’t met the others. Some things I had done parallel to the Beats when I wasn’t aware of them. In some instances I thought they were naive or posers, a justifiable concept introduced by skateboarders. (I broke my ankle on one in 1965, so maybe I was pre-punk!) Basically, I was in my own time, always. Neal Cassidy even said I had a thing with time.

So it was a case of parallel lines that at some point switched directions and intersected.

Something like that. Some of what the Beats did I thought was silly. For instance, I ran from the cameras at the Golden Gate Park Be-In when Ginsberg did that Shiva dance or whatever it was. It wasn’t my style of dancing. I had grown up doing other moves. My nostalgia is brought on by the waning 40’s and basically the 50’s, but I am nostalgic when seeing the iconic Dylan on documentaries, though I didn’t pay much attention to him after I turned Ginsberg onto his music.

You were the person who first played Dylan’s records for Allen Ginsberg.

Yes, I had played Dylan’s album to Ginsberg who heard him for the first time. He didn’t have any noticeable reaction at the time. These things work in cycles. Mike Watt took me over to Dylan’s stage back in ’08. As I stood there, me with an old gray beard, a couple of young chicks came over to me and made me dance to Highway 61. Actually, they were too YOUNG for Dylan and didn’t know he was a superstar but said, hey, he can play good! So mine’s a case of being removed and on the periphery for a lifetime but somehow retaining the ability to move in and out of scenes.

The artist and poet Gerard Malanga had this to say about Plymell’s new book: “Eat Not Thy Mind is a modest display in size only (29 poems packed into 34 pages), filled with BIG cautionary tales of doom and destruction and memories of planet Earth the way it used to be in more innocent times with waves of glowing wheat stretching as far as the crow flies in those dreams of Kansas.” Eat Not Thy Mind can be purchased at www.yod.com.

“Driving Dillinger” is a new poem Plymell wrote since the release of Eat Not Thy Mind in April, 2010. The journey continues, as Charles says, “… in my own time.”

DRIVING DILLINGER

(for Todd Moore)

Look how it’s draggin’ I hear my mother’s words

It’s a long drag and double header

Climbing the grade bowing south to Santa Fe

Blending past the purple prairie sage

The sun is lush in skyward’s crimson rim

Far behind The Sangre de Christo

Sparks link and bellow from its stacks

Its whistle low in half-open moan

We can beat it to the next crossing, John

This V8 can outrun anything on wheels.